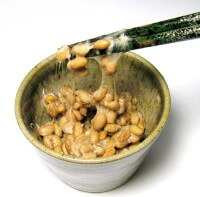

It seems fairly straightforward to us—sharp cheddar cheese from Wisconsin tastes good. Nattõ not so much. That’s because, as Rachel Herz recently explained in the Wall Street Journal, this part of everyday breakfast in Japan “is a stringy, sticky, slimy, chunky fermented soybean dish” and “smells like the marriage of ammonia and a tire fire.” There are plenty of Asians, however, who cannot fathom eating aged, moldy, and strong-smelling cheese, which Herz reminds us is technically “rotted ungulate bodily fluid” from a cow, goat, or sheep whose odor comes from the same bacteria found in our feet.

It seems fairly straightforward to us—sharp cheddar cheese from Wisconsin tastes good. Nattõ not so much. That’s because, as Rachel Herz recently explained in the Wall Street Journal, this part of everyday breakfast in Japan “is a stringy, sticky, slimy, chunky fermented soybean dish” and “smells like the marriage of ammonia and a tire fire.” There are plenty of Asians, however, who cannot fathom eating aged, moldy, and strong-smelling cheese, which Herz reminds us is technically “rotted ungulate bodily fluid” from a cow, goat, or sheep whose odor comes from the same bacteria found in our feet.

Icelanders, meanwhile, enjoy Hákarl, a shark delicacy most of us would avoid:

It is traditionally prepared by beheading and gutting the shark and then burying the carcass in a shallow pit covered with gravelly sand. The corpse is then left to decompose in its silty grave for two to five months, depending on the season. Once the shark is removed from its lair, the flesh is cut into strips and hung to dry for several more months.

Hákarl has a pungent, urinous, fishy odor that causes most newbies to gag. An extremely acquired taste, hákarl was described by the globe-trekking celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain as “the single worst, most disgusting and terrible tasting thing” he had ever eaten.

Herz, the author of That’s Disgusting: Unraveling the Mysteries of Repulsion, explains, in short,

We learn which foods are disgusting and which are not through cultural inheritance, which is very much tied to geography. One reason that certain foods carry so much local meaning is that they capture something essential about a region’s flora and fauna. The same is true of the microbes that make fermented foods possible; they vary markedly from one part of the world to another. The bacteria involved in making kimchee are not the same as those used to make Roquefort.

We also use food as a way of establishing who is friend and who is foe, and as a mode of ethnic distinction. “I eat this thing and you don’t. I am from here, and you are from there.”

In every culture, “foreigners” eat strange meals that have strange aromas, and their bodies reek of their strange food. These unfamiliar aromas are traditionally associated with the unwanted invasion of the foreigners and thus are considered unwelcome and repugnant. Conversely, a person can become more accepted by eating the right foods—not only because their body odor will no longer smell unfamiliar and “unpleasant,” but because acceptance of food implies acceptance of the larger system of cultural values at hand.

And even though most of us like cheese, we will still draw the line when it comes to, say, the casu marzu of Sardinia, otherwise known as maggot cheese. I really don’t want to explain that one.