Way, way back in June 2007, I met up with food celebrity and author Ted Allen in midtown Manhattan. We started out at the MoMA cafe, which was still bustling at 3 in the afternoon. Allen, a journalist by background, sympathized with me as a reporter (tape-recorder in hand) and suggested we find a quieter spot (and I’ll add less snooty) to make transcribing easier. So down the street we went, and not two minutes pass before fans come up and ask to get a picture with him. (He happily obliges.) Queer Eye for the Straight Guy had just come to an end after five seasons, and Allen was a star. He suspected his dark-framed glasses gave him away (he’s tried wearing hats, to no avail). Still, he didn’t mind all the attention. And he was a bit relieved the show was done. “Some of [his costars] can get a bit loud,” he said. We settled on Bar Americain, Bobby Flay’s restaurant, on 52nd Street.

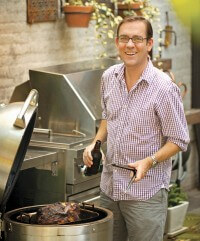

Today, Allen is the host of Chopped on the Food Network. Both he and the show are nominated for James Beard awards. The photo, taken more recently in his backyard while he was smoking a pork shoulder, is from his upcoming book In My Kitchen: 100 Recipes and Discoveries for Passionate Cooks (Clarkson Potter) due out May 1.

TA: I’m so fortunate. From the beginning, when Queer Eye started, I worried how the foodie world would receive me because my job was to deal with people who knew nothing about food, and I wasn’t a chef. My job was sort of to serve as a concierge or sort of a bridge between a lunk who knows nothing about food and fine dining and trying to make him look one step more sophisticated. And I never knew, I was never sure how that would go over among the cognoscenti in the business, and actually people have been just uniformly sweet. It’s opened so many doors for me—I’ve presented at the James Beard awards the last few years, which was a huge thrill.

VM: Was wine your first area of expertise and then you went over to food?

TA: Not really, no. I was a generalist, a front of the book editor, I wrote serious stories and I wrote celebrity profiles. I wrote fashion stuff. I published in both Chicago and Esquire. But at Chicago magazine I got more interested in serious food because that’s the restaurant bible of the city or always was and so I was always getting invited to restaurant openings and menu tastings and that’s how it started.

VM: You’ve always been into food?

TA: I mean I’ve always liked to cook but I guess just cooking hamburgers and cakes from boxes and I remember a moment when I was having dinner—I ended up doing reviews for the magazine—sort of like a junior league critic.

VM: How old were you at the time?

TA: Well, I started when I was 28, so probably around 30, 32. I went to dinner at the dining room at the Ritz-Carlton—

VM: —And you’re how old now?

TA: I’m 42 now. The chef there at the time was Sarah Stegner, who is an amazing chef, and she served a dessert. It was some sort of chocolate cake and paired it with a sweet white dessert wine. And the light bulbs went off, the way food and wine pairing could be this incredible alchemy. White wine with a chocolate cake? I would just never have understood how that would possibly make any sense. And it’s just been endlessly fascinating for me ever since.

VM: Talk about your involvement on Top Chef. They obviously came to you because of the whole Bravo connection. Can you describe that experience?

TA: It’s different this year. I’ve got about six episodes of Top Chef this season so I’m kind of a regular member but not in every episode, but more than ever before. The first season of Top Chef—that was 2005—well, Bravo, as [President] Lauren Zalaznick has said to me a couple of times, she likes her kids to play with each other, with different shows. Bravo likes to swap their people around on their programs. Tom Colicchio has guested on Top Design. Other people have crossed over between the other shows. It just made sense for Bravo to get a chef. Well they had made Runway, and it was successful. At the time, I imagine, they were hoping just to leverage a little bit of Queer Eye’s luster over into Top Chef because Queer Eye was going great guns at the time. And naturally I jumped at the chance to be on Top Chef. They also were very kind, and they helped me plug my cookbook. They engineered a challenge around my cookbook in which the contestants had to cook for a book party, which was very generous of Bravo to do that. They were very supportive of my book, for sale on the website. I got a trip to San Francisco. Got to hang out with some Mondavi friends. And it was the same production company that did Project Runway, which I thought was very well done.

I don’t love reality competition shows. I don’t like being involved in voting somebody off the island.

VM: But that’s the nature of the show. It has to be that way.

TA: I’ve kind of come to terms with it now because of that. Everybody knows it going in. But people know coming in that it’s a competition. One person has to win and fourteen have to lose. But the way I deal with it is I am respectful. I’m not overly sarcastic.

VM: So you try to be the nicer of the guys. Because I don’t know if you saw the first episode but Tony Bourdain is there calling one guy a son of a bitch.

TA: Well see, because of that, Tony is better for television in many ways than I am. And Tony, of course, there’s only one, and his wit is incredible…. He’s insane, he’s profane, he’s very knowledgeable, great chef.

VM: I was talking about Bourdain with the folks at Food Network yesterday. And by the way they say they like you too because you did Iron Chef.

TA: Oh yeah, I actually was in half the episodes of Iron Chef last time as well.

VM: What do you think about the format of these shows. Is it just a fad or just the beginning? Is this just how our food culture naturally evolves?

TA: I think Food Network was really smart that they… There have been celebrity chefs for some time now, before there were celebrity TV chefs, there were all these, you know, your Daniel Bouluds, your Eric Riperts, they were serious culinary stars, but only among the rarefied elite who were deeply into food and who could afford to eat at their restaurants. So with the exception of Julia Child, who was the progenitor of all of this, the Food Network really kind of created the phenomenon of the celebrity chef. And what was so smart about the way they did it was that they cultivated a stable of star talent. If you look at Bobby Flay being one of the best ones, if you look at their sister company HGTV, which is in far more households, HG, for whatever reason, to me their shows look inexpensive and they don’t have anybody you recognize. Can you name one person?

I can name a couple just because my boyfriend and I are psycho. I’ve watched them install a toilet fifty times. I know how to install a toilet. Why did I watch it again? I don’t know. And I heard they are changing. That HG wants to build a stable of star talent because that’s what resonates with viewers. TV viewers want stars. And people who don’t even know the names of all the shows on Food Network know who the stars are. Look at all the stars they made.

VM: Beforehand we only knew a handful of celebrity chefs from TV like James Beard, Julia Child, Jacques Pépin, the Galloping Gourmet (Graham Kerr)—

TA: —and James Beard and Galloping Gourmet were not household names. They had constituencies on PBS or wherever it was their shows ran. But it was still [not] the mass cultural phenomenon it is now.

VM: And if you go to the bookstore now, you will find shelf upon shelf dedicated to more than 30 food celebrities—

TA: —and 30,000 more who want to be.

VM: Exactly. What happened? Was it FN at the right place, right time. Was it Emeril?

TA: I think it was a couple of different trends coming together. There was the—and I would credit Martha Stewart also with a lot of this growth in America’s interest in good food and entertaining at home and wanting to learn how to do some of this stuff—

VM: —More so than at any time before. More Americans than ever want to learn at least some aspect of haute cuisine.

TA: Part of it, I would imagine, is the impact of globalization. Americans are interested in eating food from all over the place now and not just New Yorkers and Angelinos but people in Topeka. In the 1960s, the only fine food there was was French—which was what Julia did, and if it weren’t for Julia, we wouldn’t have done that. Americans now know about great coffee, Americans are interested in good cheese—

VM: It’s not like it’s a cycle, as if we knew a lot and then we didn’t, and now we know a lot again. I think this is it. A real sort of cultural turning point.

TA: Yeah, I mean people like Martha help people understand the pleasures, if you’re lucky enough to afford it, of gracious living and having a nice home, and entertaining people in your home and doing it in style that you can do it—the message is you can do it. That interesting food is part of it. But then the Food Network—I analogize it to MTV. MTV is not about music anymore. MTV began as a network that was about music. They’ve now evolved into more of an entertainment network.

VM: When you turn it on, there is no music.

TA: Yeah, it’s actually now about extremely good-looking people hooking up—and more power to them. Food Network was much more instructional and foodie-oriented in the beginning, and I imagine there are probably some hard-core foodies who don’t like it as much as a result of that. But Food Network smartly figured out that the money is in entertaining people. So you take Iron Chef America, which I think is a magnificent show, really, really smartly done. The production company is Triage Entertainment—you might want to talk to them. You should talk to Steve Kroopnick, a delightful guy. He’s one of the three principals of the company.

VM: I just saw where they film Iron Chef America. It is supposedly the Food Network’s toughest show. It takes two days to prep, and the audience is invite-only.

TA: Yeah, they’ve grown the audience area over the last couple of seasons, but everybody asks me if I can get tickets. If I’m judging, I can. But they took a culinary competition—the Japanese version was hilarious as well—but Triage and Food Network turned—it’s like a basketball game. And I can’t tell you how many people I meet who tell me their five-year-old kid loves the show. It’s funny. Alton [Brown] is delightful. He’s like that wacky science teacher. You have all these stars—Bobby, Mario—everybody knows these guys. They’re lovable and fun to watch and theatrical and the challenger chefs, the ones who are really smart are the ones who bring something theatrical to it. Ming Tsai, I think his ingredient was duck, which is a wonderful ingredient to have. He brought an air compressor and inflated the skin when he did the Peking duck, blew the skin out. I mean, that’s good TV. I judged a recent episode where they also brought in mixologists and paired them with the chefs. The mixologist Tony [Abou-Ganim] brought a still. He brought a copper stove-top still, and he distilled his own Aquavit or something on camera. They turned it into something really—it has culinary integrity, but it’s also a sporting event.

(To be continued)